Walking with Tim Rich, poet

The writer shares his thoughts on commercial writing and poetry and the thread that runs between

“Poetry opens us to the entire universe of language and how you can do extraordinary things with words – beautiful, loving, sensuous, unsettling, argumentative, wilful, revealing, unifying, subversive, strange, kind things.”

Tim Rich is a writer and communications consultant whose impressive 30-year career spans journalism, publishing, ghostwriting and commercial writing.

He’s helped leaders communicate through periods of profound change, including crisis, and his writing includes everything from a New York Times Bestselling book to comms strategies, company visions and values, manifestos, brand narratives, websites, and tone of voice programmes.

Tim and I met on a Dark Angels Masterclass at Merton College, Oxford where we partnered with another participant to invent a new word1. As chance would have it, we discovered we were neighbours, which gave us the chance to get to know each other over the 12 years since we met.

Tim’s an incredible writer – both in his commercial work and poetry – and also one of the calmest and kindest people I know. He was an early encourager of The Writer’s Walk and offered me his ear when I was first thinking of launching this endeavour. So it’s a true pleasure to share his story here.

Hi Tim, thanks for chatting with me. We’ve known each other for a long time, so for the benefit of our readers, please introduce yourself

Sarah, thank you for inviting me on The Writer’s Walk.

I grew up in the wilds of the Sussex Weald, then lived in London for decades. Now I’m by the sea, in Hastings.

I started as a magazine journalist, writing about design, advertising and photography – an early break that I still give thanks for, often. I got my first editorship at 24, under a brilliant ex-Fleet Street managing editor. That position forced me to learn fast and edit like an assassin.

By my early 30s, I’d had enough of managing people rather than writing, so I moved into copywriting and wrote a magazine column. Since then, I’ve added other types of commercial writing to my skills, from speechwriting to book ghostwriting and editing.

I hugely enjoy writing for other people – it’s a fabulous job – but poetry is my one true writing love. Of which more later, I think.

Your commercial writing career spans a wide-range of forms – from telling brand stories and helping CEOs communicate during times of crisis to speeches and ghostwriting. Is there a common thread to these different formats and styles of writing?

The common thread is the process: I obsess about the client’s readers or audience. Who are they? Why should they care about us? What do we want them to think, feel or do as a result of reading our words? I work hard to be a strong connecting point between the two. The rest is structure.

If you know how to listen closely and are adept with the elements of style, you can write across many different formats. Just add a sprinkle of confidence, I guess. My first professional speechwriting job was for a CEO in the midst of the world’s biggest news story. I knew I could create what was needed, even though I’d never written a speech before.

“I obsess about the client’s readers or audience. Who are they? Why should they care about us? What do we want them to think, feel or do as a result of reading our words? I work hard to be a strong connecting point between the two.”

In recent years you’ve moved from commercial writing to poetry and photography – often combining the two. When creating this way, what comes first – is it a word or phrase that you later pair with the right photo, or does the imagery steer your words?

With my poems, it usually starts with a phrase I see or that springs into my mind. Then, it’s as if the raw poem wants to move through me and I must invite it in and give it shape. To rework a line from Mary Oliver’s poem Wild Geese, ‘the world offers itself to your imagination.’ If I start with ‘I’m now going to write a poem about topic x,’ it rarely goes well – the words feel forced.

With my photographs, it’s about noticing small details in the margins of our world – perhaps something weathered or unloved. I’m an unschooled, instinctive taker of lo-fi images, and I don’t feel comfortable saying ‘I am a photographer’. That noun is heavy. The verb-led phrase ‘I take photographs’ feels about right.

If I combine a poem and image, it’s usually because there’s some resonance between them after I’ve made the work. I’m not interested in photographs illustrating words or words captioning images; I’m looking for a mutual exchange of energy. With my Landfall series, shown at The Bloomsbury Festival, the photographs of upturned boat hulls came first. Then, one night, a film voiceover sounded in my head and, ultimately, that turned into a poem. I suppose those hulls had something more to say.

“With my photographs, it’s about noticing small details in the margins of our world – perhaps something weathered or unloved.”

You’re a very fine poet – and I think many people might consider brand writing and poetry as two very different things. Do they feel different to you, or are there places where the two connect?

Thank you; that means a lot coming from you.

Is it simplistic to say brand writing is to poetry as design is to art? One has a function or objective, the other has a dizzying but precious freedom.

Great brand writing shows how words can connect with millions of people, many of whom might not think of themselves as readers. You find vibrancy and down-to-earth wit in copywriting – especially good ad copy. Brand writers are also adept at transforming something complex, like a large organisation or a breakthrough in science, into clear, useful content. It’s helpful for poets to see how a writer can get inside something so practical and huge, then compact its essence into a few simple words.

On the other side, brand writers can make use of how poetic elements such as rhythm, intense concision, metre and metaphor shape a reader’s experience. For example, a poem can be a profoundly intimate and moving exchange between two strangers. Poetry opens us to the entire universe of language and how you can do extraordinary things with words – beautiful, loving, sensuous, unsettling, argumentative, wilful, revealing, unifying, subversive, strange, kind things. Poetry starts with the infinite, then you bring in constraints to give it form. This is something the Dark Angels courses teach so cleverly.

It’s been a joy to see your poetry come to life over the last few years. Your poems unfurl gently – as if you’ve written them to be read slowly and savoured. Is that intentional, or is it something that happened naturally as you worked on your craft?

That’s interesting to hear, Sarah, especially your sense of unfurling – a lovely metaphor. There are a few poems of mine that start fast and sharp but, now you’ve said it, many do have a softer beginning, yes.

I am taken with the idea of inviting a reader into the world of the poem, rather than throwing them in headfirst. This might be a subconscious desire to get away from the din of attention-grabbing language in our culture.

You’ve brought to mind a poem of mine that was published recently in the American journal Stone Circle Review. It’s called Retreat and begins:

I wanted to live quietly in a white stone cottage far down an unhelpful track that twists and dips low into old black woods so unbidden guests will turn back on themselves ...

It’s an unfurling, of sorts – I start by sounding rather forbidding but keep implicitly inviting the reader to walk further down that track with me. The poem goes on to ask questions about the cost of retreating into ourselves. I bet many of the readers of The Writer’s Walk will recognise this tidal push and pull: the need to connect with others, so you keep growing, but also the desire to be alone and free to imagine, to create, to simply be.

“I am taken with the idea of inviting a reader into the world of the poem, rather than throwing them in headfirst.”

What piece of writing are you most proud of, and why?

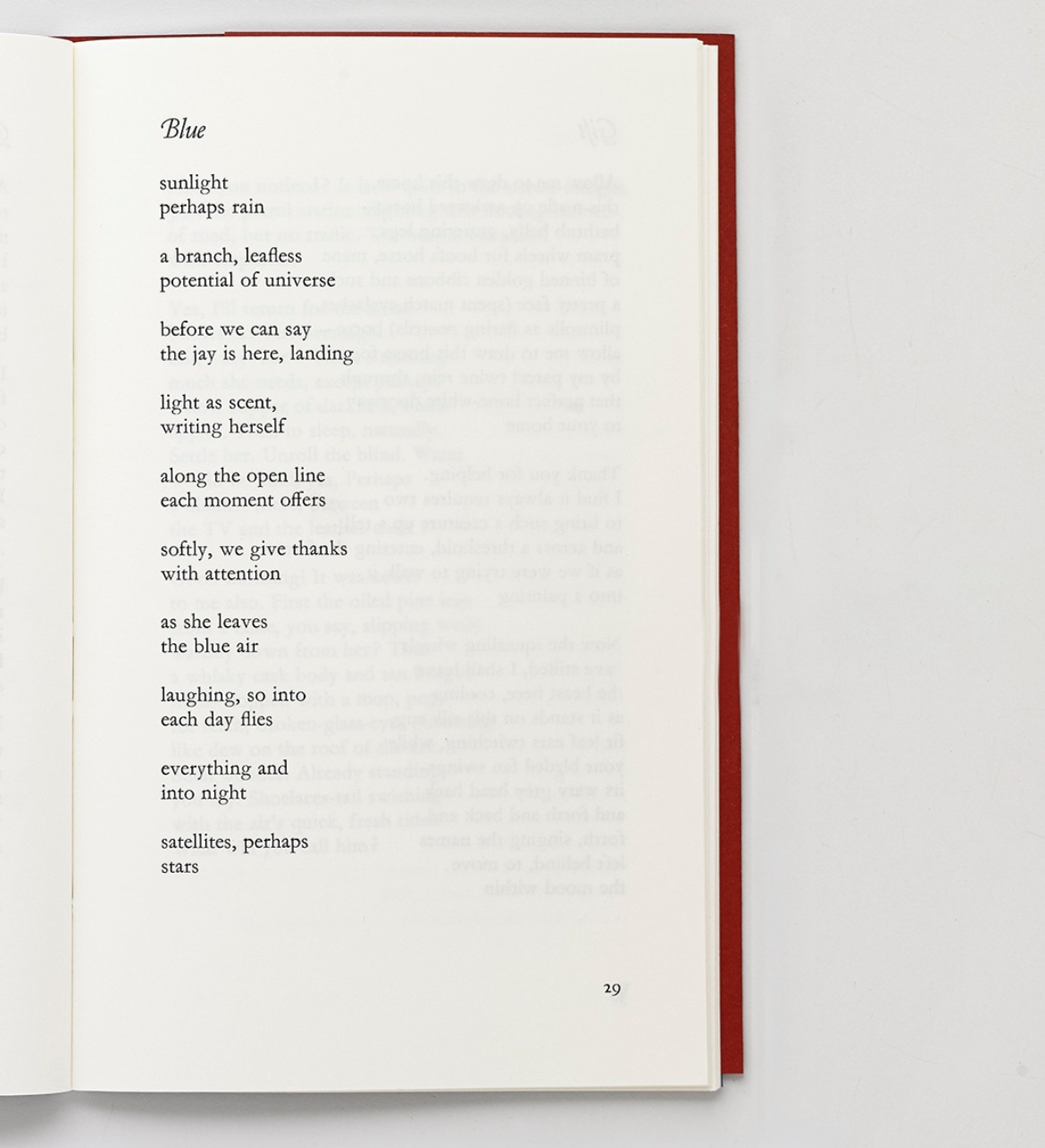

There’s a poem called ‘Blue’ that has come to hold significance for me. It was included in the anthology Dark Angels: Three Contemporary Writers (Paekakariki Press) and has now been seen thousands of times online. So, jays are a special bird for my wife, Lesley, and me. One or more often appear at important moments, and we’ve learnt to pause whatever we’re doing and take in this presence. The poem is partly about leaving space for small wonders to visit your day, and I’m delighted it has found so many readers.

Has walking ever played a role in your writing life? If so, how?

Yes, I’ve often taken short walks to clear my writing head and long walks to think about a big new project. I’m just reading about how the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, when he was writing The Wanderer and his Shadow, might walk for up to eight hours a day alone. I would often go out all day, deliberately following the most obscure footpaths I could find or wandering around industrial areas. But then something happened to change all that.

I’m guessing this is when you were diagnosed with ME/CFS?

That’s right, and I’m aware this is a condition you know very well. I was hit by a virus in 2019; by mid-2020 I was knocked flat. Since then, I’ve been making a very, very, very gentle recovery. But I can’t walk far yet – if I edge even 1% over my energy limit I go into an utterly awful crash that may last for days.

Now, instead of striding far and fast, I go slowly and take in more of what’s around me. I’ve started to see how much both light and temperature change on just a short walk. You strike up more conversations and meet dogs, cats, foxes, badgers, horses, birds. I’ve just noticed that a handsome crow spends hours each day sitting – almost still – on a neighbour’s balcony. At first, I thought it was a decoy bird.

I saw that, in your conversation with Sarah Jane Butler, she said she has ME/CFS too. She makes the point that ‘writing poetry is great if you’re not well. It’s short and you can keep coming back to it and see it new each time.’ That’s so well said; it’s why writing and reading poetry can be a godsend for creative people with chronic conditions. More broadly, I’ve learnt to edit my day ruthlessly, so I focus on the important things.

What’s your walking style – headphones or head in the clouds?

In the clouds, face towards the sun, leaving space for things to come.

What’s your most memorable walk?

In Sussex, there’s a huge area of fields and woodlands that has been rewilded over decades. Some rarely used footpaths wend through, getting you close to the most wonderful array of plants and animals, a river, and a lake. Before I fell ill, I did a whole day’s walk there with two old school friends, and it was a perfect little adventure, including having time to really talk to each other. We only passed one person. If someone would like to know where this tiny paradise is, they’re welcome to drop me a line. It’s near a train station.

If you could take a walk with anyone, real or fictional, alive or gone, who would it be?

I love exploring a new village or town with Lesley, just slowly seeing what we encounter, perhaps doing some benign trespassing. Same if we find a riverbank to explore, or a hidden beach. I especially love Pett Level at low tide and the wild coastline of the Mani Peninsula in Greece – a country I know you have a deep connection with too. If I was to add a guest to those wanderings, it might be the American writer Camille Paglia; we met her a few years back, and she’s brilliant company. Maybe we three stop at a remote pub on our walk and run into a motley group of poets playing bar billiards – perhaps W. B. Yeats, Mary Oliver, Louise Glück, John Donne, Kabir.

“Instead of striding far and fast, I go slowly and take in more of what’s around me.”

One word round

One thing you always take with you on a walk?

AnticipationOne word to describe how you feel about writing?

EnergyOne word to describe how you feel about photography?

Noticing

Can you share a walking- or photography-inspired writing prompt for our readers?

This Unloved Thing

Take a very slow walk, looking out for something odd, ugly, weathered or abandoned

Make notes about the thing while you’re with it (sketch or photograph too, if you like)

As you’re doing this, imagine how you might convey the character or essence of this thing to a friend

As soon as you get home, give yourself 25 minutes to write a short poem of 10 lines about the thing – write freely, don’t try to perfect it

Make a cup of something delicious

Give yourself 25 minutes to edit your piece

Immediately, send your words to a good friend and invite them on a walk

Sarah, thank you again for inviting me on. I thought it might be appropriate to end by sharing a new poem of mine that features walking.

The Long Lanes by Tim Rich We used the word tramp of him and it was the walking we meant: the freedom to move on again, not his stained tarpaulin hedge-tent or bus shelter naps, snoring under rain Grandma, who seemed to know more than she was saying, did once remark Well, at least those old shoes of his bring seeds from across the county so, then when I saw flowers and herbs growing by the paths he took rampions, hawkbits, eyebright, clover pimpernel, poppies, fennel and thyme I thought of him as a quiet gardener of the long lanes, fresh ideas of colour falling from his cracked boots He’s dead now, of course she said years later, while chopping rhubarb from her council plot, and I wondered had he been found somewhere or did he simply never return?

Thanks Tim, this has been the loveliest of chats and you’ve been so thoughtful with your answers to my questions – and incredibly generous to share one of your poems here.

Tim’s poems are available through Paekakariki Press and if you’d like to buy a print of his poem, Landfall you can get in touch with him direct.

I’ll leave you with this invite to walk, in Tim’s words, with your ‘head in the clouds, face towards the sun, leaving space for things to come’.

Happy walking and writing until next time.

Sarah

More from The Writer’s Walk

If, like Tim, you want to walk slowly to take in what’s around you, you might enjoy this post about walking in silence.

Sadly, ‘oxyfugilacious’ has yet to make it into the dictionary but we live in hope!